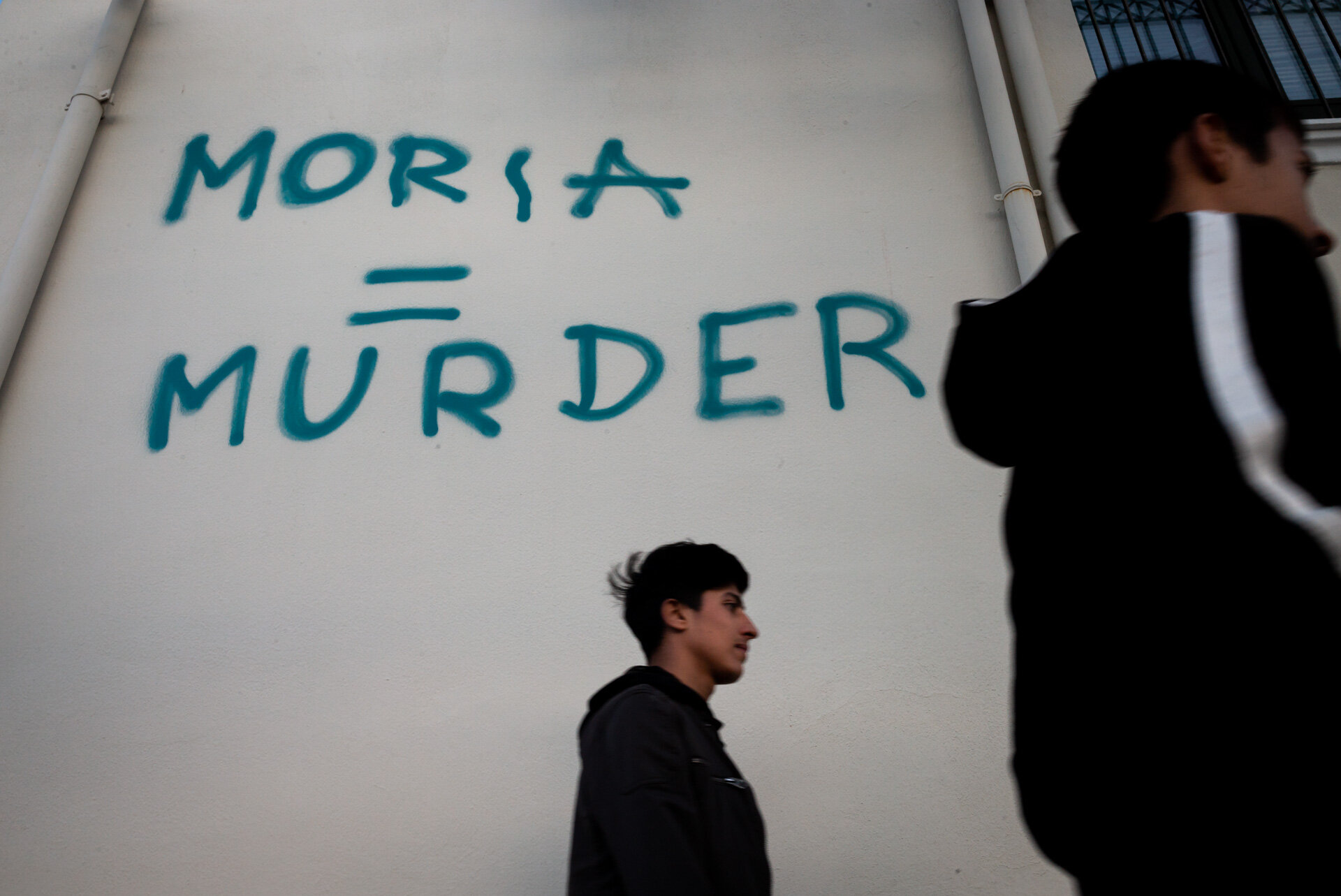

CAMP MORIA an interview with JELLE KRINGS

Jelle Krings (b.1989, the Netherlands) is drawn to issues of inequality and individual or collective injustice and suffering. Through his work, he attempts to achieve empathy and understanding for these issues and the people dealing with them. His images explore the boundaries between journalism and art. In his latest project, ‘Moria; portrait of a refugee camp’, he is documenting the inside of refugee camp Moria, located on Lesbos Island in Greece. Camp Moria is a migrant facility with a capacity of around 3,000 that is currently overrun by more than 20,000 refugees, who are trapped in cruel circumstances due to restrictive Greek and European policies towards migrants.

In an interview with GUP, Krings reveals his approach as a photographer and the harsh reality of camp Moria.

Afghan mother and her baby in 'the Jungle', outside the official camp Moria. The official camp is meant to accommodate the more vulnerable migrants such as families with pregnant women or young children, but now the amount of migrants on Lesbos is so high that even the most vulnerable are forced to sleep outside in makeshift tents. If migrants are lucky, they manage to obtain one of the few pallets available to pitch their tents on. This helps to keep the some of the cold and water outside. Not everyone is that lucky however.

A patch of refugee camp higher up the hill in the olive grove outside the official camp Moria. Life in the camp slowly picks up again as migrants come out of their tents after a full day of heavy rain. The olive grove outside Moria gets muddy when it rains, which it does about every other day in autumn and winter. The makeshift tents provided to the migrants are not built for these kind of conditions and get wet inside. Residents sleep on the cold, wet floor at night. As a result many of the residents are sick, especially the children.

Why did you decide to travel to Greece and photograph in camp Moria? For how long did you stay there?

We have all seen the images of refugees crossing the Mediterranean in rubber boats during the influx of 2015 and 2016, when more than a million migrants attempted to enter Europe by sea, fleeing war and destruction in their home countries. I wanted to find out what happened to them after they had survived this dangerous journey.

It turned out that most refugees end up stuck in limbo, trapped for years on islands and migrant centres along Europe’s southern borders, waiting for their asylum procedures to get through. Camp Moria is the biggest and most notorious one of those camps. I wanted to see for myself how Europe was treating these people, so I packed my bags and set off. I ended up staying there for three weeks, moving in and out of the camp and connecting with many of the families living there.

Life Jacket Graveyard - more than 150.000 life jackets of migrants that entered the EU via Lesbos shows the magnitude of the current crisis.

Fahim, a refugee from Afghanistan and resident of camp Moria on Lesbos, standing behind the fence surrounding the camp. Although the fence is cut in several places, allowing free travel in and out of the official camp, many migrants feel trapped. Until their asylum procedure is completed, they cannot leave the island. This can take years.

Could you explain to our readers what have you witnessed in the camp and what particularly caught your attention?

Before you can even see the camp, there is the smell. Driving up to Moria with the windows open, the scent of open sewer enters your nose. Instantly, you understand that you are going to end up in a ruthless place. The camp has a capacity of 3,000 but is currently inhabited by over 20,000 people. Those for whom there is no space in the official camp, pitch a small tent in the olive grove surrounding it, a place commonly referred to as ‘the Jungle’. Tents are cramped together in the mud and garbage and human facies lie scattered throughout the camp. Three square meter tents are shared by families of up to six people for the duration of their stay, which can take years.

The people staying in camp Moria have often lived through the horrors and dangers of war, only to end up stuck in a place that is even worse than where they came from. One of the families I followed, the Ashori’s, fled Afghanistan because of their ethnicity. The Ashori’s are Hazara, a Shiite minority in Afghanistan that is persecuted by the Taliban. Mr. Ashori told me they owned a big house with many rooms and a garden. The Taliban burned it down, and brutally murdered some of his family members. When I asked Mr. Ashori about the camp, he started to cry. Tears roll over his cheeks while he tells me that he came to Europe to save his family and give his children a future, but that Moria is even worse than Afghanistan. “I am more afraid for my children’s future now than ever”, he says, “I don’t know what will happen to them here.”

Camp Moria is a dangerous place. A few Greek police officers are patrolling during the day, but they leave at nightfall. Gangs of criminals have a free game then. Fights, muggings and stabbings are common, and women have to be escorted to the toilet after dark, or risk being raped. My translator tells me stories of suicide attempts by hopeless people, who don’t see any other way out. People are stuck. They cannot move further into Europe, but they also can’t go back. Their only option is to wait and survive.

Migrant girl in the bus from Mytilini to camp Moria. Mytilini is a small harbour town of 38.000 people. Migrants who get picked up at sea by the coast guard are dropped of here and transported to Moria by bus for the registration process. The number of refugees arriving on Lesbos increased again in 2019. In December, more than 100 refugees arrived every day. Once migrants are admitted to the camp, they are free to move around on the island, but there is only one public bus line available between camp Moria and the nearest town Mytilini for the 19,000 people living in the camp, effectively constraining them to the direct surroundings of the camp.

'The Jungle', the olive grove outside the official camp Moria. The official camp Moria has a capacity of 3000 people. Those for whom there is no space inside the official camp, have to pitch a tent in the olive grove surrounding it referred to by residents as 'the Jungle'. At the end of 2019, there were more than 19,000 people living in and around camp Moria, meaning over 16,000 people were living in makeshift tents in ’the Jungle'. Around half of those people are children. Around 70% of the residents is from Afghanistan, 13% from Syria, 4% from Congo and 4% from Somalia (According to information from Movement on the Ground, an NGO working on Lesbos).

In relation to the global outbreak of the coronavirus, would you say that the camp is prepared for such a threat?

If the coronavirus was to reach the camp, this would be a disaster. Even the most basic precautionary measures are impossible to take for anyone in the camp. Five- to six-member families share tents of three-square meters. Bigger tents are shared with other families. There is only one water station for every 1300 people, soap is in limited supply and sanitation is a huge problem. Up to 160 people on average have to share one toilet. Many people and children, therefore, opt for the bush. In addition to that, the immune systems of most people in Moria are already severely deprived. Many are sick or weak as a result of the living conditions in the camp and the cold, wet winter season that just passed. If they were to get infected with the disease in Moria, where medical facilities are inadequate, their chances of survival aren’t great. The only solution would be to start evacuating refugees as soon as possible and spread them out over the EU member states.

Children playing in 'the Jungle' after the rain. Around 50% of the residents of camp Moria are minors. Doctors without Borders has stated that the number of minors with depression and suicidal thoughts is alarmingly high.

Afghan girl holding up her baby sister in the olive grove outside camp Moria. Babies as young as a few days old live in the tents outside Moria.

Your images can be considered as an observation and a documentation of what you have encountered in the camp. How would you describe your way of photographing and what is your goal with the project?

The first day I arrived at the camp, I left my camera in the hotel. Just being there and experiencing the camp without the urge to take images helped me to connect with the people and understand the place. During the three weeks I stayed in Lesbos, I spent my time primarily with a few families. Connecting with them helped me tell the story through their eyes, and it established the trust needed to get meaningful images.

In every project that I do, my purpose is to transfer the human connection and empathy that I feel on the ground through the work that I create. I believe it is that feeling that has the power to activate people and eventually stimulate change. My goal is to evoke empathy, because if people can’t relate to others, they won’t care what happens to them.

People gathering in an open space in 'the Jungle' after the rain. The place, situated in the middle of the olive grove outside the official camp Moria, serves as a social meeting place for the refugees living in the camp.

Afghan woman in her tent in 'the Jungle'. Depression is a major problem among the residents of Moria. Poor conditions of life and the fact that migrants have to wait for up to years for their asylum decision is causing severe psychological conditions such as depression, suicidal thoughts and panic disorders.