WORDS FROM DAD - Laura Chen

Laura Chen is a Dutch image-maker currently based in Birmingham, the UK. She is fascinated by documenting her daily encounters and whereabouts, using her camera as a device and tool to make sense of the world. Anything can inspire her work and train of thought, from mundane things in her immediate surroundings to personal and contemporary issues. Chen shoots both analogue and digital and likes to experiment with different approaches to image making and appropriation. She occasionally works with found or archival images, exploring mixed-media art and traditional photo montage techniques to articulate her thoughts and ideas. Her series 'Words from Dad’ is an ongoing project that explores her Chinese heritage. With the use of archival images from her own family albums, she traces back her mixed roots through her grandfather’s life stories as told by her dad.

In an interview with GUP, she reveals the intriguing details of her heritage and approach to photography.

Could you please explain to our readers the main story your dad told you about your grandfather?

My grandfather Tek Suan Chen was born in 1910 in Wenzhou, China. He was a dignitary and the Chen family were judges and landowners there. Everything had been taken away from them, their possessions and their lives. The whole family was killed by the communists during the Mao Revolution. My grandfather was the only one who survived together with his teacher and cousin Bun Chen. My grandfather was just 23 years old when he fled, as a student, from Wenzhou to Europe, via France to Germany. Due to the political consequences of the war he eventually ended up in The Netherlands. He first started a Chinese restaurant in Amsterdam on the Rokin. In this period, he met my grandmother Helena Blockpoel in The Hague. He then also started a wholesaler on the side in The Hague. Probably to be closer to my grandmother. Because he worked in his restaurant four days a week in Amsterdam, he was not much at home in The Hague, therefore, he sold the restaurant in Amsterdam at urgent request of my grandmother. In 1946 they got married.

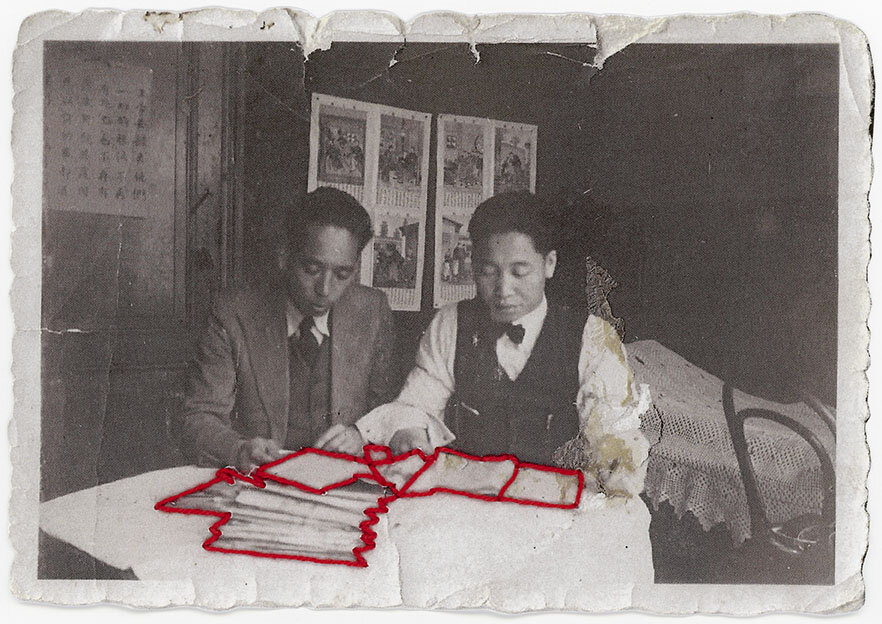

During the German occupation, Chinese were accused of being spies, just like virtually every group of foreigners at that time. It was not just accusations that my grandfather experienced. Even before the war he wrote in all kinds of student magazines to inform his compatriots in the West about the events overseas. In such articles he expressed himself in no uncertain terms about the war between China and Japan. His nephew Bun Chen had a radio transmitter and receiver in the back of the wholesale business and so they could follow the news closely. These were sufficient reasons for the Dutch police to accuse them of being spies and to detain both of them in prison for two days. In the meantime, the wholesale trade was cleared.

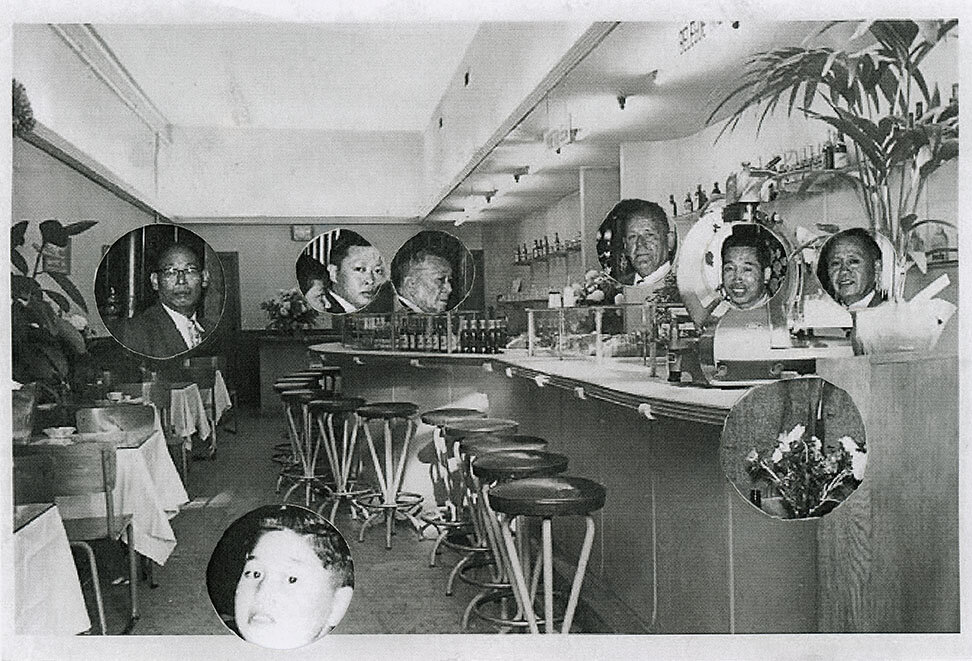

On the 24th of September 1947, my dad was born. Two years later in 1949, my grandfather and his associates opened the first Chinese restaurant in The Hague, called Ling Nam, on number 95 in the Wagenstraat. The status pioneer comes to Tek Suan Chen.

The names of the associates; Chen, Yang and Tseng. Ling Nam was a success in The Hague and beyond from the moment it opened. It was known for quality and cosiness (in Dutch ‘gezelligheid’). After the retirement of the three companions, Ling Nam was sold in 1975.

At home as a child, my dad often asked my grandfather about what it was like in China and about his childhood and family. Also, whether he would ever want to go back to visit his birthplace. He never wanted that; we think because of the traumatic memories of his murdered family. His nephew Bun Chen went to visit his son Wha Hou Chen and returned to Wenzhou. He said my grandfather's family home, the house and the temple, are still in their original state with the same interior. In 1959 my grandfather got the Dutch nationality. He received news from China that he could officially claim his family home, but he never wanted to.

As a student, my grandfather had mastered many dialects. He also mastered calligraphy with Chinese ink and brushes on original rice paper which his friends brought with them from China. As a child, my dad could study and observe him for hours when he was practicing his calligraphy. My dad tried to imitate him with brush and ink as best as he could. Very often my grandfather would paint Chinese characters for friends on paper lanes, which were glued to the inside of a restaurant window so that the painter outside could precisely copy the outlines. He was also frequently asked by the immigration service as an interpreter and translator, because even many Chinese people could not understand each other nor understood Dutch. My father found this very amusing as a child, because he did not understand anything of the Chinese language himself. Unfortunately, he was not raised bilingual. It was funny when his school friends were at his home as they could understand my grandfather with difficulty (due to his accent). It turns out my dad had no problem with his pronunciation, because it was a kind of second language for him that he had grown up with.

Your photographs sometimes contain embroidery or are composed into collages. How would you describe your process behind creating your images?

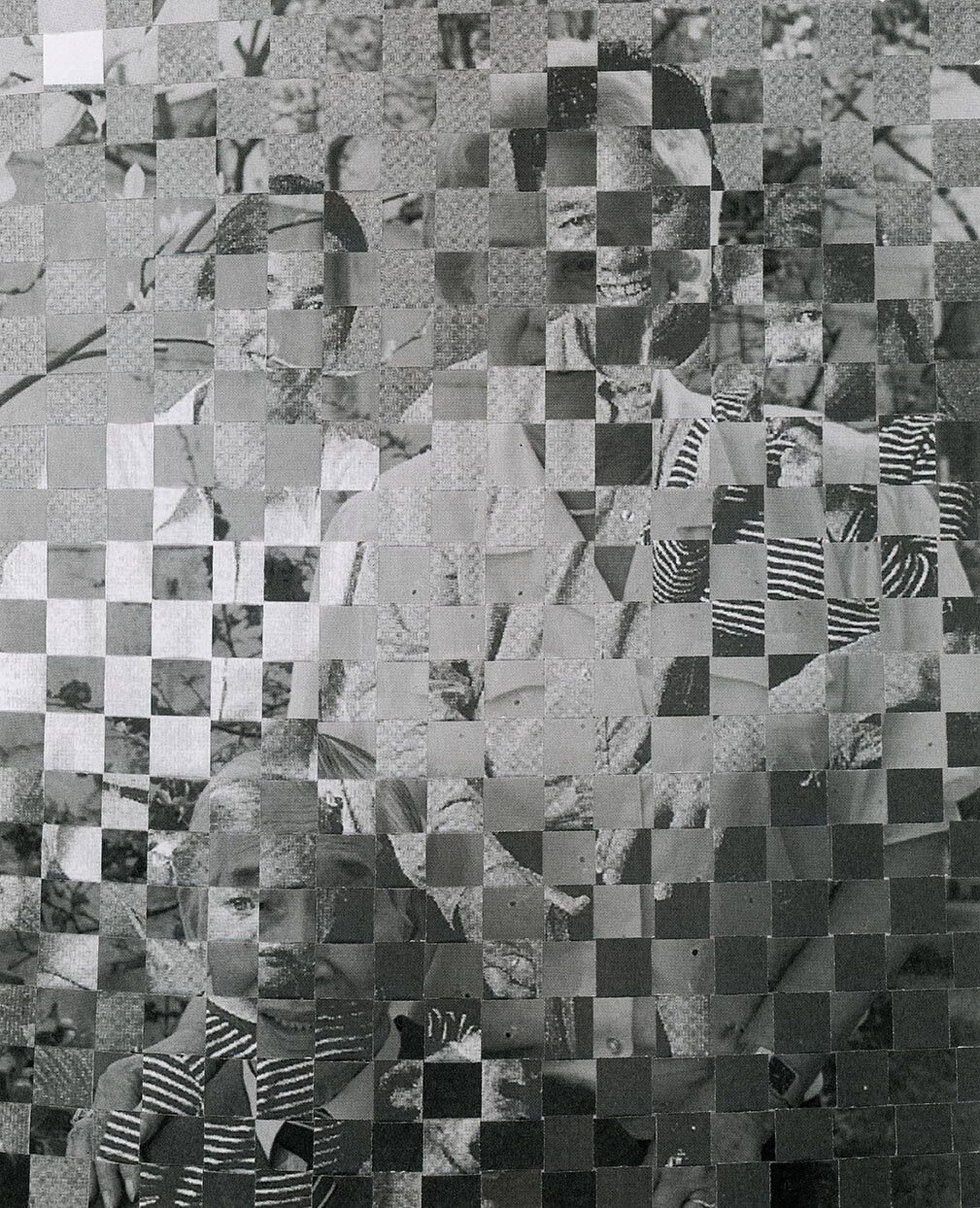

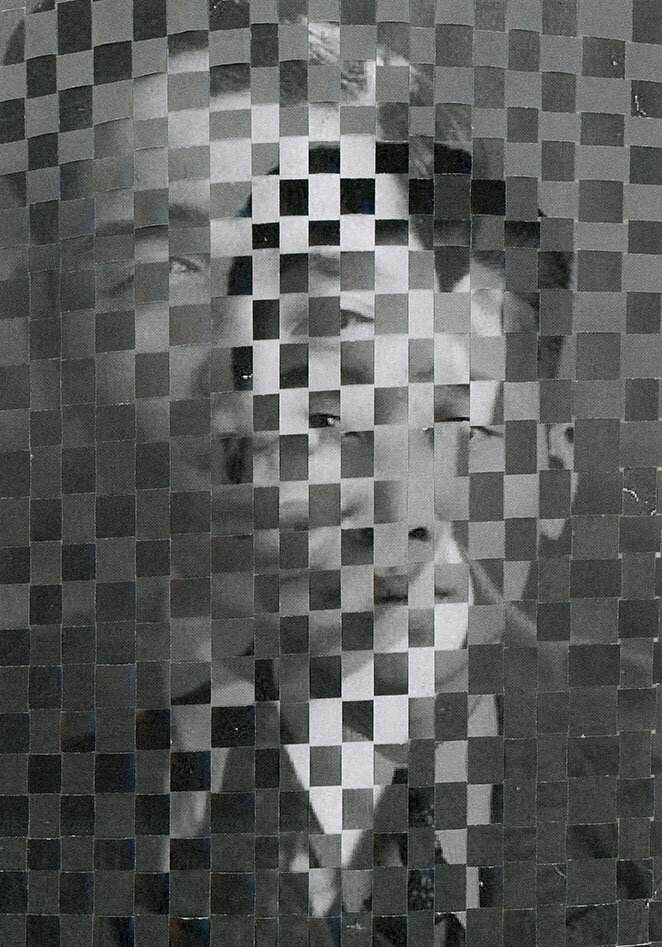

My image making practice involves applying analogue photo montage techniques such as weaving, which is used as a metaphor and visual representation of my grandfather's experience of adapting to a new (Western) culture and of my father's multi-cultural upbringing. In a way I am literally weaving together these different cultures, creating a fusion of their Chinese and Dutch identities.

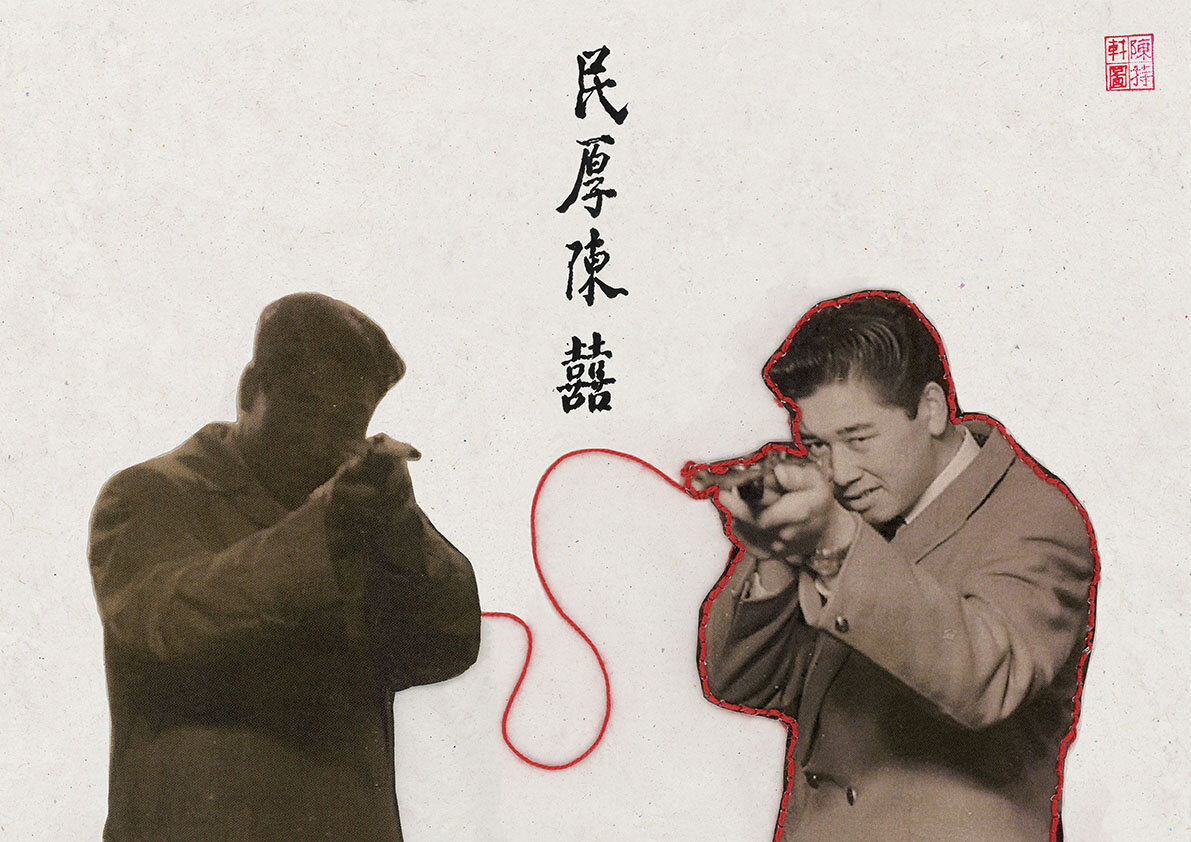

Some of your photographs are weaved with a red thread. What is the symbolism of using this technique and specific colour?

Throughout the series, I also explore the ancient Chinese belief of the invisible ‘Red String of Fate’, not only because it is part of Chinese culture, but also because it encapsulates a universal story of love and destiny. According to the legend, two people connected by the red thread, are destined to meet each other, regardless of place, time, or circumstances. The magical thread, which is believed to be tied around the ankles, may stretch or tangle, but will never break. The myth is similar to the Western concept of soulmates. I believe the story perfectly encapsulates and perhaps accounts for my grandparents’ relationship. It seems like fate; how they met as complete strangers, from different cultural backgrounds, and did not speak the same language, yet somehow ended up together. I suppose the act of love is a language in itself that speaks on a much deeper level.

My fascination for this concept of destiny is what motivated me to apply photo embroidery. With the use of red string I create many connections within the photographs, making the invisible visible.

Since you never met your grandfather but dedicated a whole project to him, would you consider your series to be your grandfather’s monument?

That would certainly be a nice way to describe it. Unfortunately, he passed away before I was born, but I have always had a very strong interest in the stories my father told me about him (hence the title of this project). When looking through our old family albums, I suddenly got the urge to archive the photographs in digital form. The thought of losing them, and the stories and memories attached to them, started haunting me and so I began scanning the physical copies. After revisiting the scans on my laptop at a later point, the idea for this creative project was born. I really wanted to get to know more about the people shown within the images, as many of the faces were unfamiliar and thus left me with questions. Some of them had messages written on the back in different languages which we tried to translate, but they did not clarify or explain much. I wanted to obtain real facts and evidence, which is very difficult when what is left of my father’s side of the family is so small. Coincidentally, an old friend of my grandfather’s cousin Bun Chen has recently reached out to me. The man is 97 years old and had somehow found out about my project while searching the web. He emailed me some photographs from his archive, accompanied by very detailed stories about Bun and my grandfather, which he had copied from his notebook or diary. We are yet to meet up soon (hopefully) to exchange stories and look at more pictures. I am keen to build onto this existing body of work and enrich the project with new material.